Former Navy Commander Dick Nelson got a message from former Commander J.B. Souder in which Commander Souder wrote about meeting with thirteen former MiG pilots in San Diego, California, on September 21, 2017. Commander Nelson wrote:

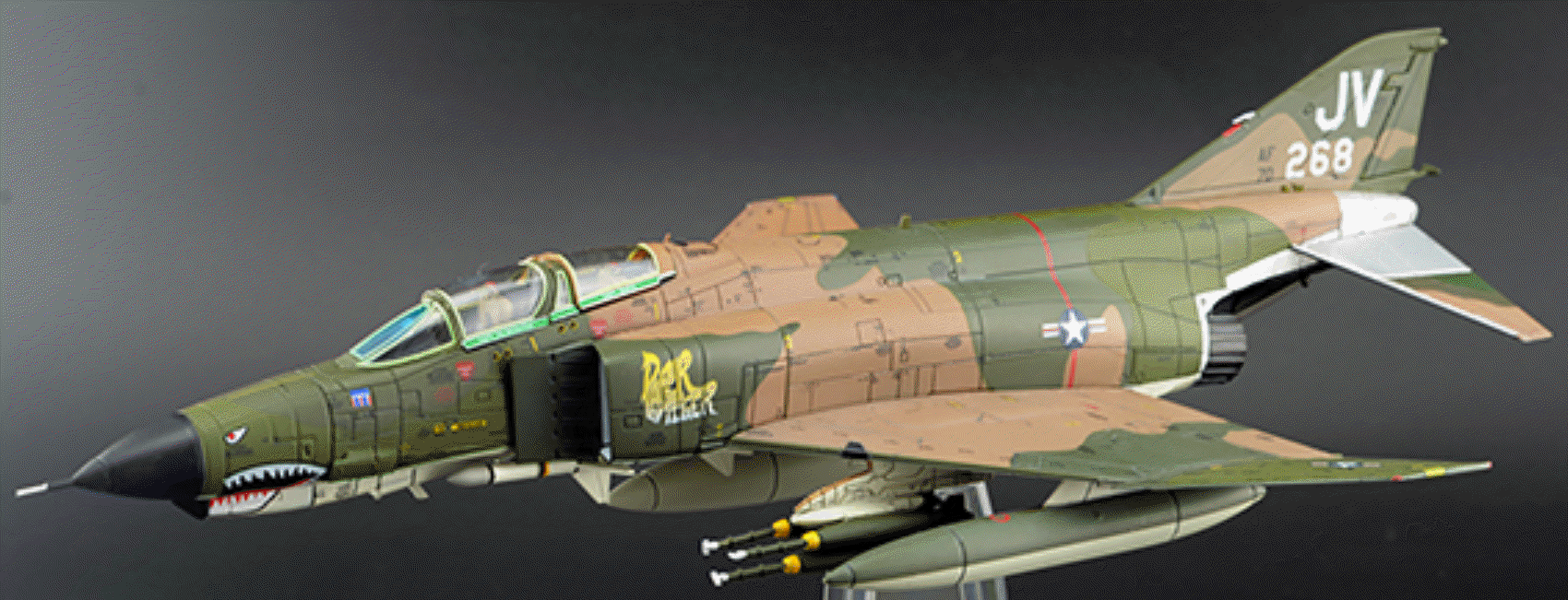

J.B. was, by all accounts, one of the Navy’s top RIOs in the F-4 Phantom II. He received the Silver Star for one of his missions, in which he saved several friendly aircraft by his tactical expertise, during a large MIG engagement. He flew over 300 combat missions, and crewed an F-4 that shot down a MIG. Ironically, a flight leader’s bad judgment resulted in J.B. and his pilot being shot down by another MIG, and he spent a tour in the Hanoi Hilton.

He recently attended a get-together with a dozen former North Vietnamese MIG pilots and U.S. pilots with MIG kills—a gathering of eagles. His narrative of this unusual meeting is truly fascinating. This is a little long, but well worth the read:

Below is the text of J.B. Souder’s very informative and interesting account of the meeting between the former adversaries.

I’m cruising along at 37,000 feet some place over Arizona. I’m headed back to Port Orange after a fantastic adventure in San Diego with some of my old fighter squadron friends and others from my days at NAS Miramar. I’ve decided to write a little recap of the event for a bunch of friends with different backgrounds so the language will vary for the benefit of those who have combat or aviation experience and others who don’t. The “facts” I’m reporting are subject to my diminished hearing and my failing memory.

About 8-10 months ago a retired Marine colonel named Charlie Tutt assembled a group of aviators to go to Hanoi, Vietnam, to meet with some Mig pilots from the war. They went, had a great time, and decided to invite the Mig drivers to come to the USA. The Mig drivers accepted the invitation and arrived in San Diego on September 20th.

Nine American former pilots and one RIO hosted the meeting with thirteen Vietnamese pilots. The Americans went out on the internet and invited any/all of us who had tangled with Migs during the war, or who were just interested in it, to attend the meeting both to get good looks at the Mig pilots “up close and personal” and to add to the stories. I went. There were about 25—30 American former aviators in all. Among the Mig pilots were guys who had flown the Mig-17, the 19 and the 21, and among them were three retired Lt Generals. Two of the Lt Gens were aces with six kills each, and the other one had four. Most of the other ten pilots had American kills. Among the Americans were navy F-4 pilots and RIOs, USAF F-4 pilots and WSOs, F-105 pilots, and two navy guys who’d flown the A-1 and A-4. Our navy Phantom crew who made ace, Randy Duke Cunningham and his RIO, Willy Driscoll, were there. Six American former POWs were there too, four Air Force and two navy. My dear friend Bob Jeffery was there. Bob was a USAF F-4 pilot who got smoked on his FIRST mission on December 10, 1965, and spent the next 7 & 1/2 years in Hanoi. Some of the Viets brought their wives as there were five or six women there too.

The event opened with a meeting in the conference room of the Holiday Inn Bayside at 0830 on Thursday the 21st. A rostrum was set-up in the front of the room with a microphone and the American and Vietnamese flags properly displayed. There were several cloth covered round tables which seated ten each situated all around the room, each with note pads and pens at place. There were coffee and ice-water urns in the rear of the room. The Vietnamese pilots and American crews mixed and schmoozed the first half-hour or so until the meeting was formally opened by Charlie Tutt who sort of MC’d the whole day.

The idea was for the pilots who had actually engaged each other in the air to form panels to discuss what happened then to brief all of us on the events after they got all their lies….uh….er….facts straight. Several were able to identify each other so they met at the two front tables and with the aid of interpreters got their stories and events synced up. After about an hour they went to the rostrum and told their stories by one pilot talking a few minutes then the interpreter doing her work, then the other pilot taking his turn talking with the interpreter doing her work again.

The first interpreter was a woman who had to interpret a stranger-than-usual southern Vietnamese dialect into a northern dialect so the other interpreter could understand before translating it into English. Needless to say, that process was laborious and we lost a lot of the meaning, sentiment and emotion while it took place. One interesting thing though, was a long session with 82 year old Sen.Col. Nguyễn Văn Bảy, the most highly decorated Vietnamese Mig-17 pilot. He got 7 kills and became “a national treasure” so Ho Chi Minh pulled him out of combat and limited him to instructing for the next few years. Van Bay was the spittin’ image of Ho Chi Minh himself, incidentally…

After an hour and a half lunch break we had a new interpreter who did a much better job and everybody seemed to enjoy the stories much more. That interpreter was a former Mig-21 pilot, now airline Captain Nguyen Nam Lien who flies 787 Dreamliners for Vietnam Airlines. Before the afternoon session began I introduced myself to him and I was startled to hear him say “Oh yes, I know you, we have met before”. I asked him when-where-and how and he said he’d been the AirBus pilot who flew me and “Jeremy” Morris from Hong Kong to Hanoi back in 2000—-17 years earlier— when Jerry and I went over there trying to meet-up with the guy who Jerry and I helped bag back in 1967. That guy is the infamous (now retired Lt General) Mai van Cuong…one of Vietnam’s three pilots tied for 2nd leading ace of the war.

Jerry and I had stopped to chat with Lien as we were getting off the AirBus in Hanoi and Lien remembered us by name! Lien had written a book in Vietnamese about all the air-battles between the US and Vietnamese and had detailed descriptions of each one (at least as detailed as he could get) from combing through tons of official records in Hanoi, American military libraries and books authored by credible American and foreign writers, as well as personal interviews. It was interesting to have him read about both of my encounters with Mig-21s to me. The one intercepting van Cuong was sketchy but factual and the one which told how Hoang Quoc Dung (pronounced Zoong) intercepted me was virtually the same as which Zoong had told me—but it was a lie. Zoong told both Lien and me that he climbed to about 15,000 feet while heading south to meet us then after sighting me he swooped down to my six (behind me) and smoked me with an Atoll, a heat-seeker missile. I knew it was a lie because the Vietnam Airlines AirBus captain who took Jerry and me back to Hanoi in 2006 knew Zoong personally and he told us what really happened. The truth was that Zoong came at me from a head-on intercept, flying under the almost solid undercast, then did an Immelmann up to my six o’clock and shot me. I’d told people for years that a 2nd Lieutenant on his familiarization-two flight could have shot me down for all the degree of difficulty it was. My flight-leader, the most exalted fighter-pilot the navy had ever known, led us right into a trap and handed us to the Zoong on a silver platter. Anyway, after that “personal” session with Lien he opened the afternoon session and did a great job of translating the interesting facts of the fights.

Before he started the translations Lien took the time and made a special effort to emphasize that “Now we can finally tell the truth…all the records in Vietnam have been opened and studied for the facts and the truth is now exposed. From now on we will finally tell only the truth”. I found that to be interesting because it tacitly admitted that they had been lying in the past…or at least evading or hiding the truth. That also made me wonder why Zoong had lied to us about how he shot me down.

One revealing, and at the same time funny, story was about the lone kill the US got with a Talos missile. The C.O. of the USS Chicago forty years ago has wanted to know for years if the one Talos he fired brought down the entire flight of four Mig-17s he was shooting at that day in May 1972. I’m thinking it was the 12th. The answer is NO, it brought down only ONE Mig; and the guy who it brought down told the story. He was on his very first mission after becoming combat qualified in the Mig-17 and he was #2 in a “loose” flight of four. They were at about 18,000 feet south of Hanoi and headed south. His lead gave him a signal to cross-over to the opposite side of the formation and he did. Just seconds after he did, the missile exploded, tearing his Mig to small pieces. To say the least, he was VERY surprised but ejected successfully. Later, after meeting up with his leader again he accused him of knowing the missile was coming and had crossed him over in order that the missile would guide on him instead of the leader. We all got a big laugh out of that.

Another interesting snippet was that the North Koreans had asked the Vietnamese if they could send some pilots to fly with them so they could get some experience fighting Americans. Yes, but the Koreans had to be under the Viets’ control and fly according to their doctrine. Originally the Koreans sent 16 pilots then sent more later, and the Koreans did indeed fly against the US. There was no mention of a Korean ever shooting an American down, but there is a monument to deceased flyers in Hanoi and there are 20 North Koreans listed on it. I wonder if Kim Jung Un knows about that monument…..?

NO RUSSIANS EVER FOUGHT AGAINST US. The Russians sent instructors to Hanoi and they did fly instructional flights, but none ever flew in combat. It was against Ho Chi Minh’s wishes to get the Russians involved in actual combat. They DID provide all the Mig-21s the Vietnamese flew but they didn’t actually fight against us…except once! They didn’t say where it took place—Kep, Phuc Yen or Yen Bai, but here’s the story:

One of the Viet’s best pilots had been injured, or had been sick, and he was grounded for a while. When it came time for him to “get back in the saddle” he was paired with a Russian instructor to fly an unarmed two-seat Mig-21 to refresh his skills. Shortly after they took off they were jumped by two USAF Phantoms and the Russian was having a terrible time trying to defend against the two Phantoms. The Viet pilot was an accomplished combat pilot and took control of the plane. He masterfully evaded both the Phantoms until (I guess) the F-4s got so low on fuel they had to knock it off and departed the area. The Mig pilot landed the 21 and when they got on the ground the Russian instructor was “shaking like a leaf”. He told the Viet pilot “Alright then, you saved my life, so come on over to my place and I will give you some VODKA!!!!!!” BIG LAUGHS again by both the Viets and the US crews. That is the only recorded time any Russian did air-battle with an American [in this war].

A similar story was that one day the US attacked one of the Migs’ air fields. A 21 pilot went up against them and stayed engaged until the Americans departed. By the time the fights were over and the Americans were gone the Mig pilot realized he was out of gas and wouldn’t have enough gas to fly a regular approach and landing. So he just flew right back to directly overhead the field and ejected.

Another big laugh-getter was a short story by one of the Viets. He said that he had barely gotten into combat when on one of his very first missions he had been shot down. He said he was angry at the American pilot who embarrassed him by bagging him until he realized the truth of the situation. After a lot of thought he was able to adequately mentally insult the unknown pilot. He said he was finally able to imagine saying to the American, “OK, big deal, congratulations, that was a big accomplishment. You managed to shoot-down a private pilot”.

There was one Mig-19 pilot in their group, Lt.Col. Phùng Văn Quảng. He had only one kill and nobody there had fought a 19 so Quang gave us a brief on the 19. He said it was grossly underpowered and on a hot day they had to turn it into the wind to help get it started. He said he had a couple of occasions to chase Phantoms and F-105s out of the Hanoi area but he could never catch up to them—-he could never close the gap. He seemed a little embarrassed to be a 19 pilot. He said all the 19s came from Russia except one which they got from China. And if I heard it correctly, all the Mig-17s the Viets flew came from China too.

A lot of the afternoon was taken up by an interview with Lt General Pham Phu Thai, a four-kill Mig-21 driver. He was very animated and smiled a lot and was told a good story. He had been the Chief of Staff of the Viet Air Force at one time as was in on a lot of the “big thinking”. He said at one time too many Viet pilots were claiming kills which they could not substantiate. So, in order to keep the pilots honest, if they claimed a kill their bosses told the pilots to “bring me the tail of the airplane”. They literally had to get a piece of the plane they’d shot down. He said after they made that rule the claims died down a lot.

I told LtGen Thai that we Americans did tours in Southeast Asia then returned home, but the Viet pilots were at home and stayed at home. I asked him if he had stopped counting missions or if he knew how many he’d flown, expecting to hear a sum of several hundred. To my surprise he said he’d flown only 215 missions. I asked about engagements and he said he’d had 25 engagements, only 20 of which he would consider true dogfights. I had 334 missions in three cruises, so I still don’t understand the reason for the big difference in numbers. I did not get to talk to Thai again or I would have asked him to ‘splain….

Someone asked Thai who the Viets preferred to fight, the USAF or the NAVY. He was ever the diplomat and said they preferred the USAF as (1) they had to fly a long time from Thailand in order to get to targets in Vietnam so hopefully they were tired when they got there, (2) they brought a LOT of airplanes with them which provided more to pick-on, and (3) they stayed in the area longer providing more opportunities for fights. He said the navy just came screaming in, did their bombing job and dashed back out across the coastline to the safety of the water…much better chance for a rescue in case the plane went down. He also said a navy plane going down in the water “made it a lot harder to get the tail of the airplane”. BIG LAUGH there. At the end of his talk, in whispered tones from the corner of his mouth, he also said, “Navy more difficult”.

During another brief interview, a Viet pilot said his most dreaded adversary was the navy F-8 Crusader, that it was the hardest to fight against as it had a gun. That made me wonder if the era the Mig pilot referred to was before TOP GUN came along [when the F-4 community finally learned to dogfight].

FLASH BACK: During that first meeting back in Hanoi one of the navy guys had asked the question of the most senior officer in the group, himself a six-kill Mig-21 pilot, Lt General Nguyễn Đức Soát, (pronounced “Swat”) who were the better adversaries, the USAF or the NAVY. Soat gave a diplomatic answer too, but while the group was laughing or otherwise distracted, he whispered to the questioner, “I think we both know the answer to that”.

After that session there was a three-hour break before the “From Dogfights to Detante” night on the USS Midway Museum and another long Q & A session for the public. I’d had enough by 3:30 so I took the rest of that day off and rejoined them around noon the next day at MCAS Miramar for the air show.

The commanding general of the Third Marine Air Wing, Major General Wise and CO of the air station, Colonel Woodward, invited the Viets and their hosts to watch the air show in the “BIG TENT”. I had been invited by the CO, Marine Air Group Eleven, Colonel Simon “Simple” Doran, a long-time and highly valued friend, to do the same. There were plenty of tables with programs and there was a delicious buffet set up and a bar complete with beer, wine and whiskey, and a photo booth for souvenir photographs. They also had a huge tub of vanilla ice cream with a myriad of toppings for dessert. The Viets were all over, most of them sporting TOP GUN ball caps which Cunningham had given them, and they were scurrying back and forth to get good views of the airplanes and the jet-powered truck. Bob Jeffery and one of his side-kick pals from his Viet squadron days was there and I explained basic differences in US Navy/Marine Corps and US Air Force philosophy/policy/doctrine/viewpoints/ways of doing things to them. They both understood our ways but found it hard to believe and accept.

When the Blues took off the Viets were all eyes to the skies and you could see by their smiles and gestures that some of them were flying right along with the Blues. I sat with Lt Gen Nguyễn Kim Cách another six-kill Mig-21 pilot and I pointed out to him the tail hooks down on the F-18s as they came by inverted or during the dirty loop, and I gestured to him that I snubbed my nose at the USAF guys in the tent. He understood and we laughed. He was a charming fellow and I decided that from his stories the day before and his animated conduct now he was the most mischievous of all the Viets.

After the air show—around 5—we went over to the O-Club and Bob and his pal were once again “wowed”. Bob said he’d never seen an O-Club like that before. I told him there were none. I saw retired Lt General Tom Conant who had been the Commanding General of the Third Marine Air Wing at Miramar a few years back and who is now working for Lockheed Martin in the F-35 program. It was GREAT to see Tom again after about six-seven years and he invited us to fly the F-35 simulator they had set up in the club’s dining room. I told Tom that Bob had been cooped up in Hanoi for 7+ years so I’d really like to see Bob fly it. Bob flew it. He liked it, but he claims he just FORGOT to try for a carrier trap. Heh-Heh…..Sure…

I took Bob into the WOXOF room (a bar) and he could hardly believe the decor. The Marines have made it look like a bunker compete with one wall of sand bags and large, carved wooden plaques displayed all over the place (each time a Marine squadron goes on cruise they have a plaque made which depicts their squadron and its theme, mission and personnel). We had a grand time reuniting with old friends and around six the Viets showed up and a few minutes later the Blues showed up. They had a mutual-friends-society back-slapping session in one of the back rooms then they all came out to have some libations in the main bar and on the back patio—both of which were packed! I met the incoming BOSS of the Blues, Commander Eric “Popeye” Doyle, a long-time and close friend of Simple’s, and I took the opportunity to give him some learned advice on leading the Blues next year; I told him to not F it up! He said that was the best advise he had gotten so far and I told him I normally gave out advice too younger and lesser experienced aviators…and there wasn’t even a charge for it. He looked at me kinda funny.

The Viets left and the Blues mingled and I drank two-three-seven too many more Jack ’n Cokes and kept schmoozing, then around 9:30 I left too…and I sure was glad I had a designated driver.

I thoroughly enjoyed both the days I spent with the Mig drivers and the events were well planned and superbly executed…the host aircrew did great jobs making things happen “behind the scenes”. I must mention, however, that our pal Jack—Fingers—One Gun—Ensch seemed to do the heavy-lifting because he was everywhere at one time. I didn’t see him much but every time I looked up I could tell he’ d been there because I could see his smoke. He was in and out of minimum burner the whole time, darting all over the place assuring that things were going as intended and on schedule. At one point I did hear him say the day at the Miramar air show reminded him of taking the kids to Disneyland. I suspect Jack’s work and “attention to detail” was the primary cause the event went so well and was so much fun for the rest of us. Just like 44 years ago in Hanoi, Jack’s great personality and sense of humor made it a lot easier—-not fun—-but a lot easier—-for us to be there.

Well, we’re over east Texas or Louisiana now and my memory—-and my fingers—-are about exhausted. I wish more of my old squadron mates, the Fighter Squadron 143 Pukin’ Dogs, would have come to that interesting and “awesome” meeting with our former enemies, but they didn’t. I also wish they had come to the O-Club for reunions with some of our old navy buddies (I saw several from the two reserve F-4 squadrons at Miramar in the early ‘70s) but they didn’t. I felt very selfish having all that fun to share with only Bob Jeffrey, but I just soldiered on and endured it.

That meeting with the Mig pilots made me think of when Jerry Morris and I went back to Hanoi that second time in 2006 when we had that terrific experience of meeting with Hoang Quoc Dung: it was surreal. This meeting was a lot more fun since we got to do more than just talk and it was a lot more laughs with 13 of them. It felt GREAT to have a kind of “cathartic experience” with Zoong and it was really fun to watch the other Americans in the group as they intermingled and interrelated with the Vietnamese. All our exchanges were cautiously friendly and respectful, although you could tell there was that ever-present “fighter pilot playfulness” and people felt free to joke and tease each other a little and laugh a lot. If anyone reading this has an opportunity to mix with some former Vietnamese enemies I highly recommend you meet them and get to know them and have fun with them…they aren’t our enemies any more…

Jaybee Souder….somewhere in the free skies above the USA…

Visiting VN Pilots:

1. Lt.Gen. Nguyễn Đức Soát MiG-21 6 victories

2. Sen.Col. Nguyễn Văn Bảy MiG-17 7 victories

3. Sen. Col Lê Thanh Đạo MiG-21 6victories

4. Lt.Gen. Phạm Phú Thái MiG-21 4 victories

5. Sen. Col. Ha Quang Hung MiG-21

6. Sen.Col. Nguyễn Thanh Qúy MiG-21

7. Lt.Col. Phùng Văn Quảng MiG-19 1 victory

8. Sen.Col Từ Đễ MiG-17

9. Lt.Col. Nguyễn Sỹ Hưng MiG-21

10. Lt.Gen. Nguyễn Kim Cách MiG-21 6 victories

11.Sen. Col. Lữ Thông MiG 17/21

12 Lt.Col. Vũ Phi Hùng 921st Fighter Regiment

13. Mr. Nguyễn Nam Liên 910th Fighter Regiment—Interpreter

US Host Aircrews:

1. Curt Dose’ USN F-4J, 1 victory

2. Jack Ensch USN F-4B, RIO, POW, 2 victories, 1 loss [received the Navy Cross with Mugs McKeown ’61 as his RIO]

3. Rick Hartnack USMC F-4B

4. Jim Hoogerwerf USAF C-130B, TAC Airlift

5. Clint Johnson USN A-1, 1 victory

6. John Ed Kerr USN F-4J

7. Pete Pettigrew USN F-4J, 1 victory

8. Dave Skilling USAF F-100, Misty FAC

9. Charlie Tutt USMC F-4B

Some Others attending:

1.Winston Copeland USN F-4N, 1 victory

2.Denny Wisely USN, 1 victory

3.Jaybee Souder USN RIO, POW (the only one there to win 1, lose 1)

4. John Cerak USAF F-4 pilot, POW1 loss

5. Tom Hanton USAF F-4 WSO, POW 1 loss

6. Chuck Jackson USAF F-4, POW 1 loss

7. Bob Jeffery USAF F-4, POW 7 1/2 years

8. Jim Fox USN RIO, F-4J

9. Matt Connelly USN F-4J, 2 victories”